Only the relevant principles of metallurgy of high-temperature materials used in boilers are discussed here. The most pertinent portions are alloying elements and heat treatment processes. A brief overview of classification of steels is given first.

Classification Of Steels

Steels can be classified broadly based on the criteria given below:

1. Percentage of carbon

2. Percentage of alloying elements and carbon

3. Amount of deoxidation

4. Grain size

5. Manufacturing method

6. Depth of hardening

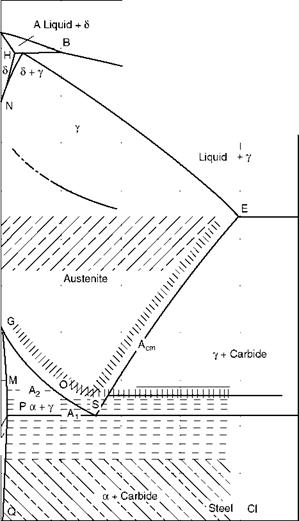

Carbon has a profound influence on the properties of steel (Figure 5.1). It has a tendency to

• Increase hardness, tensile strength, hardenability, and fatigue resistance

• Decrease ductility, malleability, toughness, machinabilty, formability, and weldability

There are three types of steels based on carbon percentage (Figure 5.2), namely

1. Low-carbon steels with 0.008-0.3% C. These are

A. Soft, ductile, malleable, and tough

B. Machinable and weldable

C. Not hardenable by heat treatment

The majority of boiler and structural steels are of this variety.

|

Carbon (%) FIGURE 5.1 Effect of carbon percentage on steel properties. |

|

Eutectoid steel

FIGURE 5.2 Classification of steel by carbon wt%. |

2. Medium-carbon steels with 0.3-0.6% C. They are called the machinery steels. They

A. Need high cooling rates for hardening and the resulting hardness is not so high

B. Are shallow hardening types

C. Are difficult to work cold and hence are hot worked

In boilers, the fasteners and shafts are of medium carbon steels.

3. High-carbon steels with 0.6-2.0% C. They are called the tool steels and are

A. Hard, brittle, and wear-resistant

B. Difficult to machine and weld

C. Hardened by heat treatment to high hardness level (the depth of hardening is also high)

Their use in boiler practice is limited to auxiliaries such as fans, mills, feeders, shafts, balls, rings, blades, and so on.

To enhance the desired properties, certain metals such as Cr, Ni, W, Mo, Mn, V are added. Based on the alloy content, they are classified as low (<10%) and high (>10%) AS. Together with low-, medium-, and high-CS, there are six types of AS. Effect of alloying elements is described in Section 5.5.2.

During solidification of molten metal, the dissolved oxygen and other gases come out as CO and are entrapped in the solid ingot, creating undesirable blowholes and inconsistent properties. Deoxidation is an effort to eliminate this effect that results in three types of steel (depicted in Figure 5.3).

• Rimmed steel. The gases are trapped at the edge of the ingot, which increases at the bottom. The thin outer rim is low in carbon and high in pure iron. It is very soft and ductile. It is also free from blowholes and segregations. Immediately underneath lie the gas entrapments with blowholes. Rimmed steel is cheaper to make and is

|

JYL |

F—"°=S F—) O •—> |

||

|

0° — °‘o |

R |

^ <=> O oO e=> ‘=> oO 4-7 |

|

|

9 2. 0 2 O o 0 0 O 0 1 O O o ° |

F i ! |

||

|

O o 1 O 0 0 0 ° s O°o <“= |

|||

|

<=> 0 ^ |

|||

|

,—, O 0 1 <=>0 O So ц 8. °S o2, F—> 0 <^7 |

|||

|

■—3 0 0 4=3 <=> 0 0 CZ3 C=> O D<3 <=> 0 0^ |

|||

|

“g? o 0 OOOOOOO CO ^IЯOЯOQ 00 | |

|

Rimmed steel Killed steel Semikilled steel FIGURE 5.3 Classification of steel by deoxidation. |

Widely used for making structural plates. It is also used for making steel strips for welded pipes. It is good for forming and deep drawing operations but unsuitable for forging or carburizing.

• Killed steel. The dissolved oxygen is completely removed by the action of strong deoxidizing agents such as Al, Si, or Mn. Although oxygen is removed, oxides are formed, which result in inclusions. Si and Mn are added in the form of fer — rosilicon and ferromanganese. The deoxidizers are added in the hot metal in the ladle before pouring. For killed steel, the big-end-up ladles are used to enable the inclusions to gather as a pipe in the middle of the ingot. Killed steels are used for items required for forging, carburizing, or heat treating. They have more uniform properties but can vary from top to bottom or core to surface of the ingot. Most CS having <0.25% carbon and AS are of killed variety.

• Semikilled steel. The deoxidation is partly done. Most semikilled steels have

0. 15-0.25% carbon and 0.05% silicon. Semikilled steels are used for plates, sheets, and structurals.

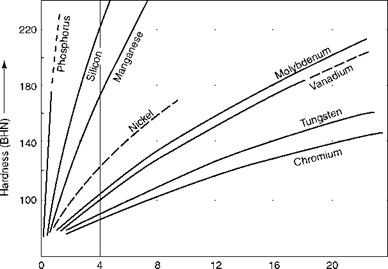

Figure 5.4 shows the classical Fe-C diagram, which is fundamental to all explanations in metallurgy.

In the heating cycle, above the upper critical temperature, all grains are of austenite and of the smallest size. Grain size increases as the temperature increases. Depending on the coarsening of grains, the steels are classified as either (1) coarse — or (2) fine-grained. Finer structures produce higher values of tensile and yield strength.

Grain growth sets in earlier for coarse-grained steel than for fine-grained steel. In rimmed steels, coarsening is rather rapid, whereas in killed steels, the fine grains are maintained for a much longer period at higher temperatures.

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

||

FIGURE 5.4

Iron-carbon (Fe-C) diagram.

Steels are made by one of the following five methods:

1. Basic open hearth

2. Basic oxygen

3. Acid open hearth

4. Acid Bessemer

5. Electric arc

The properties of steel are not particularly dependent on the manufacturing process.

Depending on hardenability, steels are classified as (1) nonhardening, (2) shallow hardening, and (3) deep hardening.

The hardenability depends on the carbon and alloy percentage of steel. Low-carbon and almost no alloy steels are nonhardenable, and are suitable for cold working and welding. Shallow hardening steels are medium-carbon and low-alloy steels hardened only at the surface, with the interior retaining its original toughness for gears, cam shafts, etc. Deep hardening CSs have more carbon and alloy content.

Effect of Alloying Elements on Steel Properties

Iron with 99.9% purity is useful only for electrical and chemical industries and as a sintering material. In this form, iron has

• Tensile strength of 215-275 N/mm2

• Lower yield strength of 88-137 N/mm2

• Elongation of 40-60%

• Hardness of 440-540 N/mm2

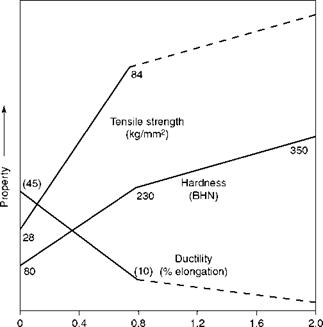

For mechanical applications, iron has to be dosed with other elements to obtain specific properties such as hardness, toughness, wear and corrosion resistance, elevated temperature strength, and so on. The effects of the most important alloying elements affecting boiler steels are given briefly in Table 5.15. Figure 5.5 shows how alloying affects hardness.

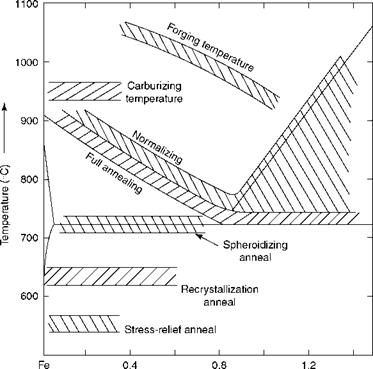

The purpose of heat treatment processes is to alter the structure of the metal to induce properties favorable to further use or processing. Table 5.16 covers the most common heat treatments involved in boiler making. Figure 5.6 depicts the various heat treatment processes with the help of the Fe-C diagram.

Certain Terms in Heat Treatment as Relevant to Boiler Steels

Aging. Holding steel at moderate temperatures, above or below room temperature, once or repeatedly (called artificial aging), to accelerate the property changes, which would have taken an extended time at room temperature (natural aging).

Austempering. Cooling the workpiece from hardening temperature to a temperature range between the martensitic and the pearlitic formations in salt or metal baths and holding there until the entire transformation is completed, followed by cooling to room temperature at any desired rate.

Austenitizing. Heating to and holding at a temperature above the critical temperature Ac1 to convert the structure completely or partially into austenite.

Case hardening. Hardening of the outer layer of the workpiece by carburizing or nitriding or both.

TABLE 5.15

Effects of Alloying Elements on Steel

|

Alloy |

Essential |

Net |

Enhances/Positive |

Reduces/Negative |

|

|

Elements |

Attribute |

Effect |

Effects |

Effects |

Remarks |

|

C |

Companion |

Tensility, yield, surface |

Impact, elongation, |

Forms martensitic |

|

|

Element of Fe |

Hardness |

And machinability |

Structure in quenched steel |

||

|

Al |

Deoxidant in steel production |

+ ve |

Resistance to aging, scaling, and heat resistance (calorizing) |

||

|

Cr |

+ ve |

Resistance to corrosion and oxidation, elevated temperature strength, wear resistance to H brittleness |

Impact, at >15% and 475°C Cr embrittlement |

>13% Cr improves atmospheric corrosion |

|

|

Mn |

Deoxidant |

+ ve |

Tensility, yield, hardenability, also prevents red-shortness |

Neutralizes S |

|

|

Mo |

For creep |

+ ve |

Tensility, yield, creep, |

Resistance to |

Used along with |

|

Strength |

Impact, wear resistance, High-temperature Strength |

Scaling |

Other alloying elements |

||

|

Ni |

For impact at low temperature |

+ ve |

Tensility, yield, toughness. High Ni reduces coefficient of thermal expansion (Invar) |

Indispensable for heat resistance |

|

|

Si |

Deoxidant |

+ ve |

Tensility, yield, resistance |

Hot and cold |

Ideal for spring |

|

And |

To oxidation and scaling. |

Workability |

Steels and electrical |

||

|

Degasifier |

At >2.5% increases brittleness |

Electrical Conductivity |

Apparatus |

||

|

W |

For high — temperature strength |

+ ve |

Tensility, yield, toughness resistance to high — temperature wear, similar to Mo. Forms strong carbide |

Resistance to oxidation |

Good for tool steels |

|

V |

Deoxidant And Degasifier |

+ ve |

Resistance to wear, strength at high-temp — erature resistance to H embrittlement |

Grain refiner |

|

|

Ti |

Deoxidant |

+ ve |

Strength at high temperature |

Stabilizer in corrosion-resistant steels |

|

|

S |

Impurity in steel |

—ve |

Machinability in free — cutting steels |

Toughness in transverse direction, resistance to weld cracking |

|

|

P |

Impurity in steel |

—ve |

Hardness when dissolved in quantity <0.2% |

Ductility and resistance to shock in CS |

|

|

Cu |

—ve |

Yield and yield/tensile ratio, up to 0.5% resistance to atmospheric corrosion |

Precipitation hardness at >0.3% |

|

Process |

Purpose |

Heating Temperature |

Cooling Procedure |

Remarks |

|

Annealing |

Remove strain hardening and |

Above recrystallization |

Controlled cooling in |

|

|

(full) |

Increase ductility mainly for cold-worked steels |

Temperature and hold for a long time till full conversion to austenite |

Furnace to <316°C |

|

|

Process |

Improve ductility and |

Below subcritical |

No grain |

|

|

Annealing or Stress Relieving |

Decrease the residual stresses in work-hardened steels |

Temperature 501-704°C |

Refinement |

|

|

Normalizing |

Homogenization and strain relief. Harder and stronger than full annealing |

Above upper critical temperature |

Air cooling |

Similar to full annealing |

|

Quenching |

Hardening of high-carbon steels to give high strength and wear resistance |

Heat to austenite |

Cool rapidly in water or oil to <200°C to form martensite |

|

|

Tempering |

Make softer and tougher steel. |

Below lower critical |

Any desired cooling |

Secondary |

|

Spheroidizing |

Remove some brittleness in quenched steel Soften and improve machinability |

Temperature Heating for a long time fine pearlite just below lower critical temperature |

Rate |

Treatment |

|

Solution |

Producing single-phase alloy |

Above solubility curve |

Quench in water or |

|

|

Treatment |

Of austenitic steels having good creep strength |

And hold long enough to attain grain growth |

Any suitable liquid to prevent carbides to reverse |

|

TABLE 5.16 |

|

Common Heat Treatment Processes and Their Effects |

![]()

|

FIGURE 5.5 Hardening effects of various alloying elements dissolved in pure iron. |

![]()

|

Alloying elements in alpha iron (wt%) |

![]() Note: Homogenization is the elimination of previous fabrication and heat treatment history. Tempering follows normalizing and quenching processes.

Note: Homogenization is the elimination of previous fabrication and heat treatment history. Tempering follows normalizing and quenching processes.

|

Carbon (%) |

FIGURE 5.6

Heat treatment processes.

Carburizing. Enrichment of the outer layer of the workpiece by carbon to make it harder by holding it above the critical point Aq Ac3. Gas, bath, powder, or paste carburizing are the various processes.

Flame hardening. Hardening of the workpiece by surface or by heating with torch.

Hardening crack sensitivity. The tendency to form cracks during hardening or in the hardened, nontempered condition.

Hardening from hot forming. Hardening in any desired manner after hot forming like rolling, forging, or drawing, without intermediate cooling below the lower critical temperature Ar:.

Holding time. The time the workpiece is held at the desired temperature after it has been heated to that level. The soaking time to reach that temperature is not counted.

Nitriding. Hardening the outer surface by heating and holding the workpiece in nitrogen-rich environment. Gas nitriding and bath nitriding are the two methods.

Stabilizing. Bonding of fine segregations obtained by annealing.

Corrosion can be defined as the destructive or damaging chemical or electrochemical reaction between the unprotected metal or alloy surfaces and the aggressive chemicals in the

Surrounding environment. The aggressors can be O2, CO2, SO2, and humidity in air, gases, and liquids, causing destruction and transformation producing salts, oxides, hydroxides, and chlorides.

There are several types of corrosions of which gas-side corrosion due to ash, namely, high and low-temperature corrosions are most common to boilers and are discussed in great detail in Chapter 3.

• Surface or uniform corrosion is the most common type. It is the chemical or electrochemical reaction that takes place over the whole exposed area. It can be prevented or reduced by (1) proper material selection, (2) suitable coating, (3) application of inhibitors, and (4) cathodic protection.

• Pitting is localized, deep, and heavy and causes craters such as under cutting or pin head-type pits in the metal. The crevices can already exist or can be formed. The cause is the formation of an oxygen cell.

Oxygen corrosion is an electrochemical process in which oxygen from atmosphere is dissolved in an electrolyte such as water, and attacks the metal surface to produce pitting. This is typically the case with boilers that are idle for long periods with water in the tubes. Highly destructive pitting is very difficult to detect, as the pits are small and are often covered by deposits. Usually pitting is localized. The failure is often sudden, calling for shutdown of the plant. Pitting is also difficult to predict.

• Selective corrosion means individual constituents are selectively attacked in alloys. The usual example is the attack of zinc in brass.

• Contact corrosion occurs between the assembled components where different metals or alloys are in contact. Electrochemical cells form and cause this type of corrosion.

• Crevice corrosion occurs under the heads of bolts, nuts, etc., due to uneven ventilation. This is an intensive localized corrosion that frequently occurs within crevices and other protected areas exposed to corrosive substances. It is usually associated with small volumes of stagnant solution left by holes, lap joints, gaskets, and surface deposits. Also, it takes place under bolt and rivet heads. This is also called deposit or gasket corrosion.

• Stress corrosion is an abrupt failure of materials that are not properly stress relieved or annealed with locked-up stresses due to corrosion. A combination of tensile stresses and corrosion results in crack formation. The surface of the metal or alloy is practically unaffected, although the cracks are progressing underneath. The separation occurs without any deformation characteristically intercrystalline or transcrystalline and without the formation of any corrosion products.

Caustic embrittlement in PPs of high-pressure boilers leading to abrupt failures is an example of stress corrosion cracking. Cracks or brittle failures used to occur in the rivet holes. Cold working caused the stress and NaOH — or caustic-aided corrosion, together produced caustic embrittlement. High-pressure and high-temperature SHs made of ss are also susceptible to stress corrosion cracking due to chlorides or oxygen.

• High-temperature corrosion, typically as experienced in SH and RH, occurs where the ash constituents attack the tubes in solid state or liquid phase. With coal, the cause is the formation and decomposition of alkali sulfates, and with fuel oils, the sodium vanadyl vanadates cause this corrosion.

• Dew point corrosion or low-temperature corrosion is typically the attack of the flue gases on the cold-end heating surface (HS) as a result of metal temperature dropping below the dew point. Sulfuric acid is formed due to the reaction of SO3 and H2O in the flue gases at low temperatures, which then condenses at temperatures lower than the acid dew point. This causes the corrosion of steel tubes in the ECON and AH.

• Vibration corrosion takes place by the combined action of vibration and corrosion. Unlike stress corrosion, the vibration corrosion can happen with all metals and alloys. It is always intercrystalline.

• Erosion corrosion is a phenomenon in which erosion and corrosion act together to accelerate the destruction due to the movement of corrosive fluid over metal. Erosion is the mechanical destruction of surface due to the presence of hard particles in a fast-flowing stream. Unlike corrosion, which is chemical or electrochemical in nature, erosion is purely mechanical in action.

Destruction due to erosion has a characteristic appearance of grooves, channels, ridges, valleys, and rounded holes created by the motion of fluid. The destruction proceeds until failures eventually occur. Most metals and alloys are susceptible to erosion. For corrosion resistance, most surfaces are dependent on developing a protective surface layer. Soft metals such as copper and lead are highly susceptible.

For minimization and prevention of erosion corrosion, the usual methods adopted are as follows:

• Use of better materials that can resist this type of corrosion

• Design change involving change of shape, geometry, and selection of materials

• Change in process by way of deaeration and addition of inhibitors

• Application of coatings such as hard facing, weld overlay, or suitable repair

• Cathodic protection, which is not yet a popular solution

Metallic corrosion can be a film-forming or nonfilm-forming reaction. The former exerts a self-inhibiting effect as the film increases in thickness. The latter is more damaging and progresses aggressively and slows down only when the attacking medium is consumed. A uniform corrosion such as rust formation is benign, whereas localized corrosion such as pitting is rapid and more destructive.

Corrosion loss is usually stated in grams per square meter per day or millimeters per year or, in U. S. practice, mil/year (mil is a thousandth of an inch). There are six levels of attack as shown in Table 5.17.

|

TABLE 5.17 Corrosion Resistance Index

|

24 августа, 2013

24 августа, 2013  admin

admin

Опубликовано в рубрике

Опубликовано в рубрике